In 1541, the Geneva city council asked Calvin and Farel to rebuild Geneva. Calvin did not want to return because he knew that his life there would be full of controversy and danger. But finally, he returned to Geneva because he knew that he was not the master of his life, he had given his heart as an offering to God. This became Calvin's motto with the icon of a hand holding a heart that is ready and ready to be offered to God.

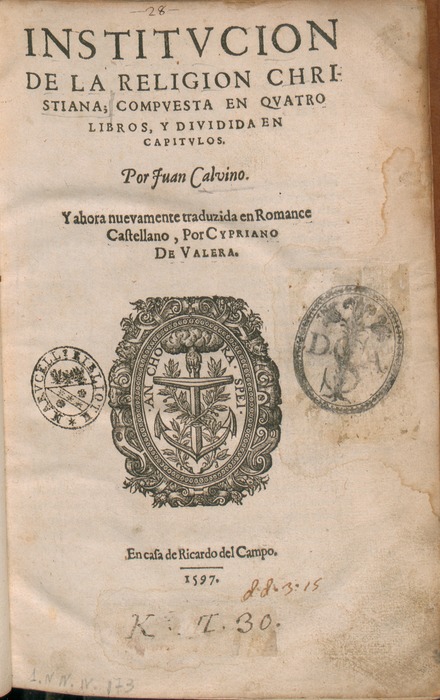

Immediately after he worked in the Geneva congregation, Calvin put together a new church order called: Ordonnances Ecclesiastiques (Ecclesiastical Code), 1541. Calvin was a great theologian in the reformatory churches. His theological views were expressed in his book, the Institute.

Calvin taught about justification by faith alone (Sola Fide), as did Luther. However, Calvin places great emphasis on sanctification, the new life for Christians who are grateful, because God has saved them. Calvin emphasized that church members who come together to hear the Word of God and to partake of the Lord's Supper must be holy. Church discipline is closely watched. Supervision of the behavior of church members is not only carried out by the elders, but also by the government (City Council).

The relationship between church and state in Calvin's theology is very close. Calvin aspired to a theocratic state. The whole life of society must be arranged according to the will of Allah. The government is also tasked with supporting the church and eliminating anything that is contrary to the pure gospel message. However, this does not mean that the state is under the church. Church and state side by side. Both have the duty to carry out God's will and defend the honor of God. Regarding the duty of the state, Calvin wrote as follows: "The government is given the duty to, as long as we live among the people, support and protect the worship of the outward God, maintain sound teaching on worship and the position of the church, govern our lives by looking to the social interactions, shaping our morality in accordance with justice as stipulated by state laws, making us harmonious and maintaining peace and general order .... "

Regarding the positions in the church, Calvin knows four positions, namely: pastor, teacher, elder and deacon. Pastors together with elders constitute a consistory, that is, a church council that leads the congregation and who runs church discipline. The regulations for the election and ordination of church officials were carefully regulated, especially the office of pastor.

Regarding the Holy Communion, Calvin taught that Holy Communion is a gift from God and not a human act. The bread and wine are not only symbols but the instruments used to give Christ's body and blood to His people. However, Christ is now in heaven. Bread and wine cannot be considered the same as the body and blood that is in heaven but must be regarded as signs and seals of God's grace and love in Jesus Christ. Calvin distinguished a sign from what it signified. Calvin explains it this way: "As the believer really received the signs with his mouth, so at that very moment he was really connected by the Holy Spirit to the body of Christ which is in heaven." In administering the Lord's Supper, Calvin was meticulous.

Calvin in his teachings also emphasized predestination as well as justification by faith. According to Calvin, from eternity God in Himself has determined which people He gives salvation and which are destroyed. Those who are chosen by God are given free gifts, while those who are rejected by Allah, Allah block the way into life. Calvin said that this was very difficult to understand. The signs that a person is appointed by God for eternal life are that he (they) are called by God and they receive justification from God. This Calvinist teaching on predestination led to a schism in the later Calvinist churches. By the time Calvin was still alive, Hieronymus Bolsec had attacked this teaching of predestination. Calvin defended the correctness of his teachings and he advised the City Council to banish Bolsec. Thus Bolsec was expelled from the city of Geneva.

Calvin also opposed the Antitrinitarian teachings taught by Michael Servet. While Servet was in Geneva on the run from the death sentence the Roman Catholic Church had imposed on him, the Geneva City Council arrested and imprisoned Servet at Calvin's request. At the suggestion of the priests and of course including Calvin in it so that Servet's head beheaded, the City Council beheaded Servet in 1553.

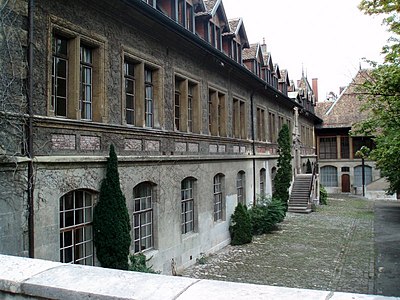

In Geneva, Calvin also founded schools. In Geneva, an Academy was established which has two parts, namely the gymnasium and theology. Theodorus Beza was appointed director of the Academy. It was at this Academy that young Calvinists who would later become well-known leaders of the Calvinist church were prepared, such as John Knox, Caspar Olevianus, the author of the famous Heidelberg Catechism.

Comments

Links